Automated hydrograph disaggregation

The hydrograph disaggregation algorithm is a means of categorizing the hydrograph into three primary constituent parts, namely:

- the rising limb,

- the falling limb, and

- the baseflow recession component.

The rising limb identifies the portion of the hydrograph that has been influenced by some forcing, typically a rainfall event, a snowmelt episode, and perhaps, some planned release of a significant volume of water from storage.

The falling limb is subsequent to the rising limb and is likely indicative of the cessation of the forcing, and thus can be though of the excess precipitation that has yet to drain from the basin.

The baseflow recession component should be though of that portion of the hydrograph that represents the slow release of water stored in the watershed. It is not uncommon to assume that this portion of the hydrograph is entirely composed of groundwater discharge, however there may be exceptions. The baseflow recession component is identified by locating portions of the hydrograph that closely follow the computer baseflow recession coefficient $(k)$ within a predefined degree of error.

Hydrograph disaggregation can be useful to hydrologic modellers needing to identify model parameters that directly relate to specific portions of the hydrograph. The disaggregation also enables the ability to isolate stream flow volumes associated with specific events and thus can be used to convert a continuous hydrograph into a discrete form (see below).

Hydrograph discretization

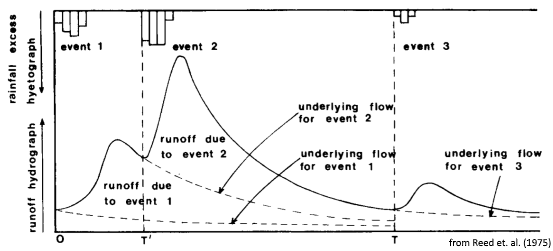

A common challenge with the interpretation of hydrology is the comparison of stream flow response to a rainfall/snowmelt event. Complications arise since stream flow response can have a greater dependence on antecedent conditions over the amount of precipitation. In addition, snowmelt events can add further complication as they are rarely measured, yet has a significant impact on stream flow in Canadian watersheds. By assuming that initial flow prior to an event is a surrogate for antecedent state, one could isolate the portion of the hydrograph caused by that particular event. This method is an extension of the work of Reed et.al., (1975) who used the method to derive parameters for their rainfall-runoff model. Arnold and Allen (1999) also refer this to the ``recession curve displacement method.’’

The algorithm locates the onset of a rising limb and projects stream flow recession from this point as if the event had never occurred (e.g., at points $T`$ and $T$ in the Figure above). This projected stream flow, termed “underlying flow” by Reed et.al. (1975), is subtracted from the total observed flow to determine the volume associated with the event. Comparing these event volumes with rainfall/snowmelt volumes can be used to calculate runoff coefficients but will also highlight non-linearities of watershed hydrology (see Beven et.al., 2011).

In particular, events may be observed in the stream flow hydrograph that may have no corresponding rainfall event on record (or vice versa). This will be problematic during rainfall-runoff model calibration as this particular event will do nothing but hinder the fitness of the model as there will be no information (i.e., data) to drive the model. Identifying and eliminating these ``red herrings’’ (Bevin and Westerberg, 2011) from a calibration data set is a crucial step in preventing model over-fitting.

References

Arnold, J.G. and P.M. Allen, 1999. Automated Methods for Estimating Baseflow and Groundwater Recharge from Stream Flow Records Journal of American Water Resources Association 35(2): 411–424.

Beven, K.J., P.J. Smith, A. Wood, 2011. On the colour and spin of epistemic error (and what we might do about it). Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 15: 3123-–3133.

Bevin, K.J. and I. Westerberg, 2011. On red herrings and real herrings: disinformation and information in hydrological inference. Hydrological Processes 25: 1676–1680.

Reed, D.W., P. Johnson, J.M. Firth, 1975. A Non-Linear Rainfall-Runoff Model, Providing for Variable Lag Time. Journal of Hydrology 25: 295–305.