Hydrogeology

Hydrogeology involves the study of the movement of subsurface fluids and their interaction with the soil and rock units through which they flow. Here we will explore how water enters the ground, moves through the subsurface, and ultimately flows back towards the ground surface. More detailed descriptions of the various aspects of hydrogeology can be obtained from numerous text books that exist on the topic (e.g. Freeze and Cherry, 1979; Domenico and Schwartz, 1990; Fetter, 2001). A more recent addition to the literature is an on-line website “The Groundwater Project” which provides ready access to many high level technical hydrogeological e-books.

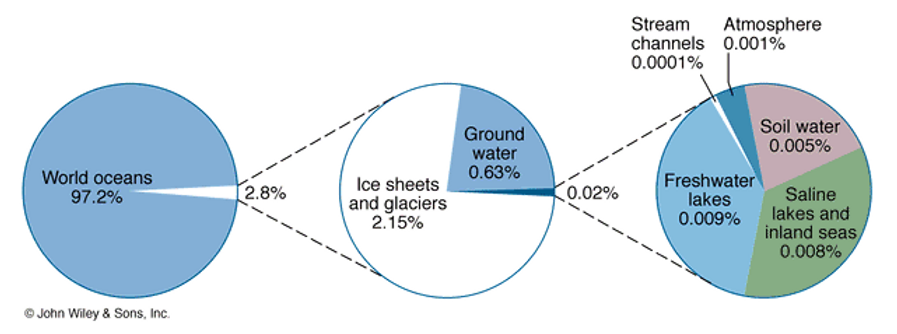

While hydrogeology mainly focusses on the groundwater component of the hydrologic cycle, hydrogeological analysis often involves an understanding and quantification of other components of the hydrologic cycle (Water Budget, Climate, Streamflow). Globally, the largest reservoir in the hydrologic cycle is the ocean which contains approximately 97% of the earth’s water. The largest freshwater reservoirs are the polar ice sheets (74% of fresh water) with most of the remainder residing as groundwater. The residence time varies directly with the size of the reservoir. Residence times in the oceans and ice caps can be thousands of years whereas in the smaller reservoirs are much less, on the order of days in the atmosphere and days to weeks in streams and rivers.

Figure 1: Global hydrologic cycle reservoirs. Figure Skinner et al.,1999

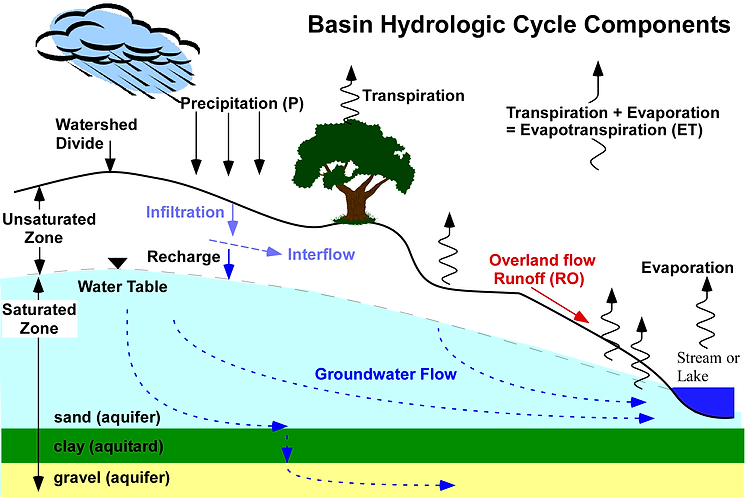

When precipitation (rain and snow) falls to the ground, the water does not stop moving. Some of the water sinks into the ground (infiltration). The Oak Ridges Moraine study area receives approximately 1 metre of rain and snow (as water equivalent) per year. On average, and noting that significant spatial variation will occur, approximately 60% of this water evapotranspires back to the atmosphere, ~25% infiltrates into the ground, and ~15% forms runoff over the land surface. Some of this infiltration will percolate to the water table as groundwater recharge. Water reaching the water table to become groundwater will then flow relatively slowly through the subsurface controlled by many factors including those related to the properties of the soil and rock (hydraulic properties) such as porosity and permeability, and the presence of differential driving forces (largely tied to topography and pressure) that cause groundwater movement.

Geologic layers or formations are often classified into hydrostratigraphic units. A hydrostratigraphic unit is a geologic formation, part of a formation, or a group of formations with similar hydrologic characteristics or properties relating to groundwater flow. This allows for a grouping into aquifer or aquitard units (Domenico and Schwartz, 1990). Fluids flow more readily through aquifer units compared to aquitard units.

Ultimately groundwater flows back to the ground surface, typically into surface water bodies such as lakes, rivers or oceans (discharge). During the journey that water particles take through the subsurface, the chemistry of the groundwater changes (water quality). Some of these changes are natural and some of these changes are human induced, for example by the introduction of contaminants. Groundwater quality analysis can tell us a lot about the flow of groundwater within the groundwater system.

Numerical modeling is another tool that hydrogeologists use to help in understanding the flow system. Numerical models are sophisticated ways of incorporating various types of measurements to quantify the flow system. By calibrating the models so that they reasonably match historical observations, hydrogeologists can then attempt to make predictions as to how the flow system may change in the future in response to various stresses such as increased groundwater pumping or climate change.

Figure 2: Components of the basin hydrologic cycle.